I am neither a mathematician nor a statistician, nor (crucially) a particularly deep thinker. And so it was that some years into my development of the bridge deal generator, I assumed that the number of possible bridge hand shapes was some hazy exponential value—certainly less than the number of unique bridge deals, but still requiring knowledge of powers of ten, the number of atoms in, if not the universe then maybe in the rings of Saturn, and other such mind-blowing expressions of vastness.

I was right about the exponentiation, except that it’s a really small power of ten—approximately ten to the 1.591, or, to be exact, 39 shapes. That’s way less than the number of atoms in the rings of Saturn, and less even than that planet’s 274 moons!

Who knew?

I could have known that if I had only jotted down the exact shapes in suit order, then noticed that they reduced quickly (by turning exact shapes in suit order into general shapes) and that after mere minutes of noodling it out, you are left with a mere 39 shapes.

As with many other things I could have learned with a bit of online research, the number of hand shapes is well documented. But I have found that the most authoritative online sources will tell you that there are 39 shapes, but they commit the Air Bridge offense of not showing you all of them.

Why? WHY? Why go to the effort of writing an article about 39 shapes, only to show half or fewer of them and then do hand-waving references to “the others”?

Here, for instance, is the hand shape explainer on the ACBL website. It starts off telling you there are 39 shapes, but then it only shows you the 14 most common. It lumps the remaining 25 (64.1025641025641% of all possible shapes!) into three categories: those with 8-10 card suits; those with 7-card suits not listed among the 14 most common; and those with 6-card suits not already listed.

Well, thank you very much! I’ll get right down to compiling my own list to supply the ones they left out, then.

Perhaps a website called Bridgehands.com will deliver the goods, in detail?

It, too, tells you that there are 39 shapes. It does a bit better than ACBL by showing you the 21 most common. But then it lumps the remaining 18 (46.1538461538462% of all possible shapes) in the “other” category.

Coolio! I only need to make my own list of the missing ones. Thanky kindly!!

From this and my frequent past complaints about Air Bridge, you know that I like to have things spelled out—served up, as it were, on a silver platter.

To the ACBL’s credit, while their website offers the abridged list of shapes, their very fine 7th edition of the ACBL Encyclopedia of Bridge delivers, on page 576, a complete list of the 39 shapes, along with their percentage frequency of distribution.

Thank goodness! A place where I can verify my own list!

And so, armed with knowledge that a) there are 39 hand shapes; and b) what they are, I of course offer all 39 shapes in the Shaper dropdown boxes of the deal generator.

Yep, 39 shapes. That covers all possibilities.

39.

That’s all we need.

Except, of course, you can see that I actually offer well over 100 shapes. Now, why might that be?

I offer 100+ named shapes of various types: shape groupings, fully-specified and partially-specified shapes, convenience shapes, and legacy shapes.

Shape Groupings

Since all 39 actual shapes are provided, you could construct your own shape groupings by using a multiple-tab recipe. For instance, on shaper tab 1 you could specify 4-3-3-3 shape; on tab 2, 4-4-3-2 shape; on tab 3, 5-3-3-2 shape. Voila! The standard balanced shapes.

However, if you then want to define point ranges and some other shapes to go with the balanced shapes, you will need to repeat those on each of the three shaper tabs.

Therefore, it makes sense to offer shape groupings for the most common shapes. So we have Balanced, Unbal, and Semi-Bal near the top of the list because they are so frequently used.

Near the bottom of the list I provide several other flavors of balanced, unbalanced, and semi-balanced, based on published sources. I added these because, early on, I had not yet figured out whether/how to limit the number of shape groupings I should define, so I added the other balance groupings as I became aware of them.

Here’s the balanced shape groupings we wound up with:

Most Common Understanding of Balanced

Balanced: 4333, 4432, and 5332. Excludes Semi-Balanced.

Semi-Balanced: 5422 and 6322.

Unbalanced: Anything not covered by Balanced.

I treated Semi-Balanced as I did because basic beginner instruction tends to focus on the three main balanced shapes and doesn’t even mention semi-balanced.

“Strict” Balanced

This grouping came about because of this article on hand shapes. I’m not sure where I got the word “strict”, but I ended up adding these shapes to the shaper dropdowns:

Unbal (Strict): Excludes Balanced and Semi-Bal (Strict).

Semi-Bal (Strict): Includes Semi-Balanced, plus 7222.

“Thin” Balanced

This grouping was loosely influenced by Terry Bossomaier’s book, Getting to Thin Games. I write “loosely” because I have not read the book (it’s on my shelf, waiting). A subscriber and expert user of my bridge dealer made me aware of some concepts, and so I wound up adding these groupings:

Bal (Thin): 4333, 4432, 5332, and 5422 (note that one of the common semi-balanced shapes joins this version of balanced).

Unbal (Thin): 6322 and 7222 (lost 5422, gained 7222).

If these groupings don’t accurately represent Bossomaier’s methods, the fault is mine.

No more Variations on a Theme of Balanced

Good luck understanding all of those in relation to each other. I supposed if you specialize in one variation or another, it’s easy enough to get used to using the shapes you need. Me, I stick mainly with Balanced and Unbal (the common variety).

At that point, without having proven the utility of those varieties of balanced, I decided I couldn’t cater to every arcane (which is not to say unreasonable) definition.

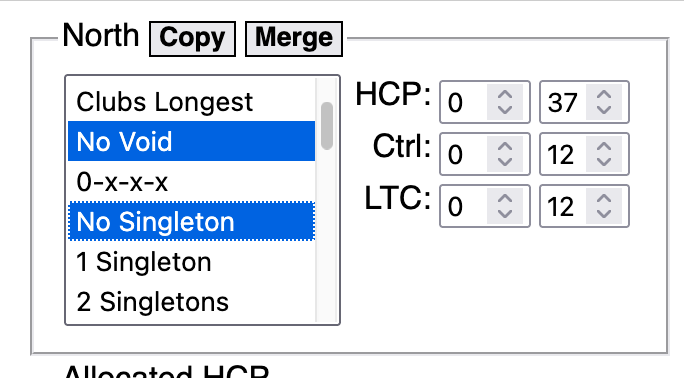

Note that the main difference between the various definitions of “balanced” has to do with the number of doubletons. If you find yourself wanting the most liberal definition of balanced, and you don’t care about what name is applied to it, you can always use the No Singleton and No Void shape selections to get no, one, two, or three doubletons:

Fully-specified and Partially-Specified Shapes

A fully-specified shape has only 4 digits separated by three dashes, i.e. 9-2-1-1. This covers the 39 possible shapes.

When you use a fully-specified shape, the deal generator will only search for a deal where the hand has that exact shape (by number of cards—not in suit order).

A partially-specified shape has digits and one or more unspecified numbers of cards, i.e. 9-2-x-x.

When you use a partially-specified shape, the deal generator will search for a deal where the hand has the exact number of cards for the digits in the shape, and any number of cards for the exes. S, for 9-2-x-x, it will find deals with one of shape 9-2-1-1 or 9-2-2-0.

I chose a rather extreme example there. You might more often use a shape like 5-5-x-x or 5-4-x-x or 6-4-x-x to partially specify two-suited hands.

I find it useful to be only as specific as necessary when creating a deal recipe. Doing so makes for more varied and realistic deals from one recipe. Being less specific also helps the generator find a matching deal more quickly.

Exact Shapes

An exact shape has an equal sign (“=”) in one or more positions, indicating that the preceding digit is an exact suit length. For instance, 1=x-x-x means exactly 1 spade, with any number of cards in the other suits; x-1=x-x means exactly 1 heart; x-x-1=x means exactly one diamond; x-x-x-1 means exactly 1 club. Note that there is no equal sign for an exact number of clubs. That’s because it is the last suit, and any digit (therefore anything other than the variable “x”) is presumed to be exact for that position.

A digit followed by a dash in suit positions 1, 2, and 3 is not exact—that length suit could be in any position, but not in another position that has a digit followed by an equal sign, and not in the last position if a digit is present there.

Hey, I don’t write the rules, I just implement them.

Rather than provide exact shapes for some arbitrary number of suit combinations, I provide exact shapes for each possible number of cards, from 0 to 13, in each suit. The exact shapes follow the “one of” shape. So for a void suit we have:

0-x-x-x means “at least one void, in any position” (no equal sign, so the 0 is not exact/positional.

0=x-x-x means “void in spades”.

x-0=x-x means “void in hearts”.

x-x-0=x means “void in diamonds”.

x-x-x-0 means “void in clubs”.

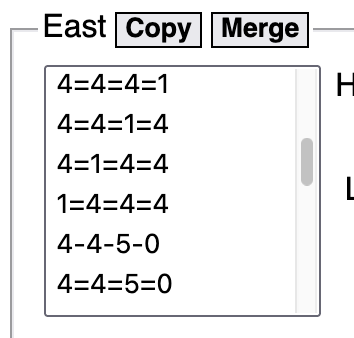

Since we have the above 5-shape pattern for all lengths from 0 to 13, I got rid of the legacy exact shapes such as 4=4=4=1 and 5=4=x-x. You can now implement them by selecting multiple shapes in one shaper tab.

4=4=4=1 becomes:

4=x-x-x and x-4=x-x and x-x-4=x and x-x-x-1. You could leave out x-x-x-1 because when you specify three exact-length suits, the fourth gets whatever is left. However, there’s no harm in including extraneous shapes if it helps convey your intent.

5=4=x-x becomes:

5=x-x-x and x-4=x-x.

Convenience Shapes

“Convenience” means making things easier. In some cases, “easier” is a huge understatement—without some shapers, you might have to make dozens of recipes with complex Card setups to achieve the same result as a single shaper selection.

Early in development of the deal generator, I had only Any, Balanced, and Unbal shapes. I theorized that anything else could be defined using one of those shapes in combination with placement of placeholders in the Cards area of the web page. You want 5332? Fine. Make a recipe with XXXXX in spades, XXX in hearts, XXX in diamonds, and XX in clubs. And another with XXXXX in spades, XX in hearts, XXX in diamonds, and XXX in clubs. And another with…

No. The number of recipes just to define basic shapes grows exponentially. Using those recipes as “starters” for more specific recipes would be a nightmare.

I reluctantly abandoned my notion of the sparse purity of the Shaper, and went all in on not only defining many more shape types, but also making it possible for the user to select multiple shapes for one hand. So, for instance, you can select Balanced, Spades Longest, and 5332 and, with nary a placeholder in sight in the Cards section, get yourself a balanced hand with 5 spades.

In those early days, I did keep trying to make the Cards area work as the preferred way to define more detailed distributions—not only shapes, but also presence or absence of specific cards. But each time I tried to do that, the Cards section setups would take on the nature of algebraic word problems. Cards solutions emerged, eventually, but they were terribly difficult to build and their meaning to another user would not be apparent at all. In most cases, I found that defining a new shaper selection made for an easy solution—easy both for the recipe writer and for other users of the recipe. It simply said what it meant.

From that experience emerged a previously-unforeseen aspect of the deal generator: providing a way, short of writing code (as is required for some other dealing programs), for everyday users to translate the language of bridge directly into a readable specification for a deal.

The language of bridge includes many phrases, and providing shapers for even just the most common ones vastly increased the size of the shaper selection list. That’s OK. Each selection (the well-thought-out ones, anyway) represents an increase in utility and a decrease in user effort.

So that’s an example of making things easier.

As for making some things even possible, see the shapes such as “No 4 Major”. That and other shapes are derived directly from the language in which bridge hands and conventions are expressed. I added them as I encountered difficulty in otherwise expressing the concepts I found when I tried to make recipes. So, while they are by no means exhaustive, they represent what I have needed in my own work.

You will see many “No” shapes, such as “No Single Face,” “No 6 Plus,” “No A,” “No K.” That’s because it turns out that negation (the absence of something) is hard to express by way of most shapers, which tend to be inclusive rather than exclusive, and placeholders in the Cards section which are, by definition, inclusive. Sure, you can overload a hand with zero-point spot cards, thus achieving “No A” (no ace), but it’s not guaranteed to work (every card has to land somewhere, and your recipe might not be airtight); “No A,” though, will absolutely work unless you foolishly assign it to every hand in every seat.

Legacy Shapes

Update: I removed the legacy shapes, in favor of Exact Shapes (see earlier section on Exact Shapes).

Early in, before I had realized there are only 39 unique shapes and before I had hit on using Shapers more extensively than using Cards, I thought I would add not only specific shapes, but that I would have exact shapes—the kind where you specify the length of each suit. So I have a few like this, with equals signs instead of dashes between the numbers:

I soon realized that I should instead provide just the 39 shapes, some groupings, some convenience shapes, and otherwise refer users to the Cards section if they wanted a very specific shape by suit. But, since I had made it possible to reload old recipes from files and links, I kept these “=” shapes around for the sake of users who might have used them in their work.

In conclusion

Shapers started out as Any, Balanced, or Unbal—true shapes, all. Now, though, the varieties of Shaper include many things that are not shapes at all. Had I known how it would go, I might have chosen a different word—something computery or scientificky-classificationy—but I have learned to go with the flow and embrace a bit of ambiguity. Thus, those things in a Recipe that are not in the Cards area shall be called Shapes simply because that’s all they were, originally.

If the purpose of a shaper is not immediately apparent, just try it. Generate some deals using only that shaper. If that doesn’t clue you in, just ask me.