If you are reading this post in an email, the links to the deal generator may not work due to the way Substack modifies them for emails. To avoid that problem, click on or near the title of this post above in your email and read the post directly on the blog.

Hi, bridge pals!

Lately I have been trying to post more about bridge and less about software development. This is a consequence of two facts: 1) most new subscribers appear to be bridge players, not software developers; and 2) the deal generator has reached a steady-state and, aside from improving the nearly-nonexistent “report” feature, I have no immediate plans for changes.

However, today I did make a change to the user interface which I will mention briefly here rather than in a standalone post.

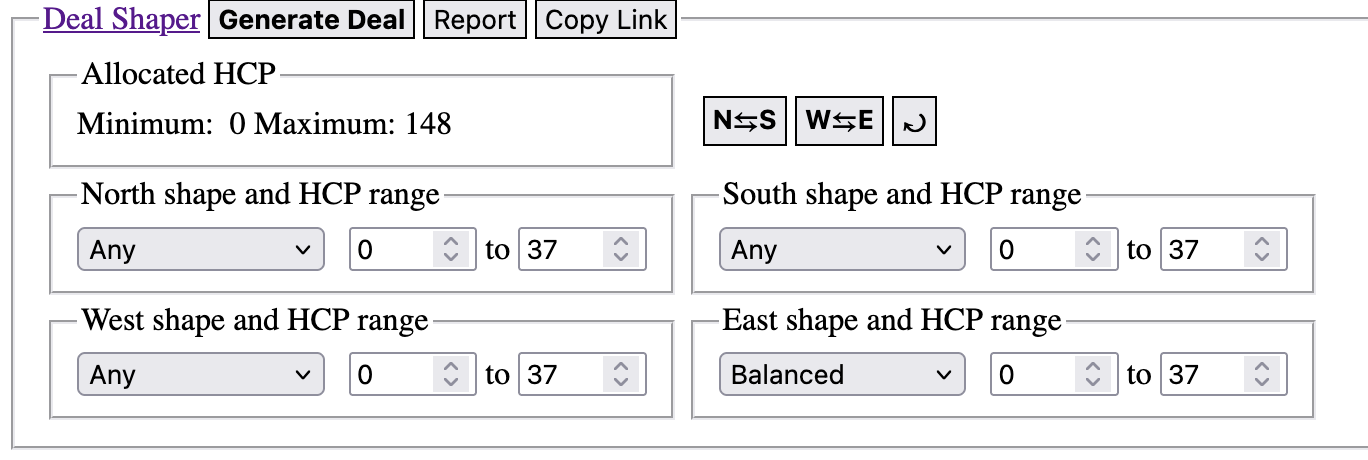

Until this morning, the Deal Shaper panel looked like this:

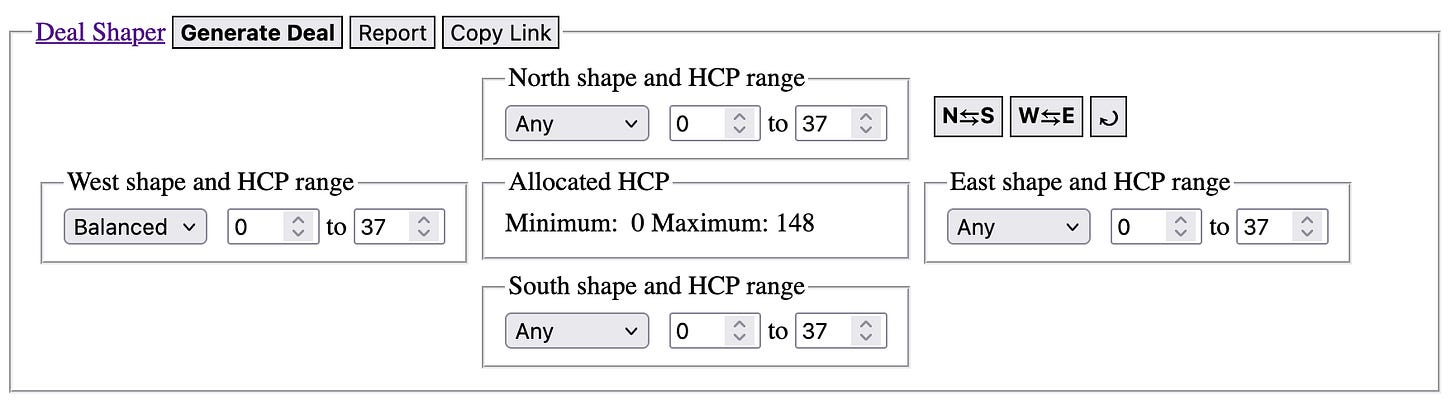

Now it looks like this:

The hands are arranged in compass order, just as in the other panels on the page and in every bridge program and article in the world. Aside from no longer having to mentally translate the shaper hands into a compass shape, you can really see the benefit when you use the swurvy-curvy button to rotate settings. Now they go nicely clockwise one seat at a time, instead of appearing to shift in some crazy cat’s-cradle pattern due to the non-compass shape.

The person who lazily designed it the first way and tried to live with it has been shown the door…

I’m back. It was me, and I just found out it’s hard to fire yourself. And now, on to a bridge topic.

You were no doubt intrigued by my subtitle, “An Antidote to Air Bridge.” I don’t recall if I have mentioned Air Bridge very often in these pages, but it is a phenomenon that was a prime reason for developing the deal generator, and making it flexible, in the first place.

Early in my bridge education (circa 2020, then Covid-interruptus, then circa 2021), I noticed that teachers and writers alike tend to present fully-worked scenarios with complete deals, or at least the hands that matter—e.g. opener and responder, in the early going (aka The Time Before Interference)—and then they explain some concept and you see it right there before your eyes and you start to get it.

But then, Air Bridge commences. Someone asks, “Hey, Teach!” (This hypothetical scene takes place in Brooklyn, or Jersey.) “Yo,” they say, “What if the ace of spades was in the opposite hand, North had a singleton heart, South had two doubletons and six clubs to the jack? I mean five to the queen. No, the jack. Hmmmm?”

Now, experienced bridge players can absorb that kind of thing and can visualize it quite easily, and off they go bouncing ideas off of each other. Meanwhile, I’m sitting there trying to write out the modified deal. By the time I get it on paper (if I get it on paper), more Air Bridge has occurred and the deal is totally different again.

I can’t fix the fact that that happens in class or in bridge articles, but I could and did make a tool to encourage good old, solid, fully-expressed deals.

This all came to mind recently as I read Chapter 9—Jacoby Transfer, of the ACBL Bridge Series book, Play of the Hand in the 21st Century. Please let me stipulate that, especially with the guidance of a good teacher, this has been one of the best, most revelatory books I have read on bridge. It is so loaded with examples that it rarely devolves into Air Bridge. While Chapter 9 has many examples, I did catch a whiff of air simply because, from page 341-347, it presents so many scenarios that it can’t possibly give a fully-worked deal for each one (or any of them).

Space and time limitations are, I think, a major reason for Air Bridge both in person and in writing. I think that if space is limited, embedding a link to a recipe or to a fully-expressed deal is quite easy (thanks to, ahem, my program) and so all authors, everywhere, should do that. And teachers should have my program up on a big screen in front of the class, and should use it to prevent Air Bridge because, after all, they can modify the recipe/deal in seconds.

Now, I understand that sea changes, revolutions, and world domination take time. So for now, I will content myself with just showing how the No Air Bridge idea would work for pages 341-347 of the 2012 edition of the aforementioned book. I will make South have the 1NT opener hand in all cases, so Souths’ shaper will look the same (balanced, with 15-17 HCP) in every recipe except where South needs to have either a minimum or maximum no trump hand.

1NT opener, partner has 5 total points and a 5-card major. (page 341)

Newbies take note! Once you click on that link and see the shaper and recipe are loaded in the deal generator, you need to click the Red Button to generate a deal.

1NT opener, partner has 9 total points with exactly five cards in responder’s major. (page 342)

Note the shaper and recipe settings for North, which are more involved than in the previous recipe. The shaper only specifies HCP, not total points. Since I know I want North to have a 5-card major, there will be at least one length point. So I set North’s HCP to 8, and in the recipe I specify five cards in either major. I then specify at least three cards in each minor suit. This rules out any accidental length points.

Holy cow, it’s almost like you really have to think when you’re making a recipe!

1NT opener, partner has an invitational hand containing a six-card (or longer) major suit. (page 342)

The “or longer” means that I didn’t limit the major suit by putting a “B” (for…man, don’t ask, I don’t know why it was “B”) at the end of the placeholders. If you put six placeholders and no length limiter, then you get at least six.

I removed the guarantee of 3 cards in each minor in North, because a 6+ card suit makes another long suit unlikely. I dropped North’s HCP to 7, knowing that they will have at least 2 length points. This helps make North more likely to be invitational, not automatically game-going (though that depends on your partnership agreement and your hand evaluation).

I gave North 9-10 HCP to keep things from getting too crazy (no easy slam bids here). I’m also back to limiting the length of the major suit to exactly five with good old “B” and using card distribution to prevent two long suits.

Page 343 discusses the difference between acceptance of a transfer and super-acceptance. I personally make that distinction by placing my bidding card on the table hard and loud for acceptance, and wafting it down gently for super-acceptance (yes, I cheat upside down). But seriously, I had not learned about super-acceptance before now.

Until now, we have kept South’s 1NT opener the same throughout, and spent our time modifying responder’s hand. To explore super-acceptance, though, we need to modify opener’s hand to suit each scenario.

1NT opener with minimum strength and 4-card support for responder’s 5-card major. Opener likely to accept transfer at two level. (page 343)

Note that, to make a minimum strength 1NT opener, you make the HCP range 15-15, aka “15” (but we always have to use ranges on the web page). Also, for the first time, I have specified placeholders in South’s hand to guarantee a 4-card major in responder’s suit.

1NT opener with maximum strength and 4-card support responder’s 5-card major. Super-accept! (page 343)

To ensure a maximum strength 1NT opener, make the HCP range 17-17.

We’re cruising along nicely. Not too bad, right? Well, brace yourself, because on page 344 there commences two full pages with countless (6) scenarios where responder is two-suited in the majors. This is the kind of thing—a long list of variations that cause me to try to memorize words without visualizing cards—that leads to Air Bridge, and I come crashing down like poor old waxy Icarus. It’s not the book author’s fault—it’s just what happens when I am given information in list form, where maybe one thing changes from each list entry to the next. There are nice single-hand examples accompanying each scenario in the book, but let’s recipe ‘em up and get the whole deal for each one.

1NT opener, partner has less than invitational strength and is five-five in the majors. (page 344)

1NT opener, partner has less than invitational strength and is five-four in the majors. (page 344)

Do you want to vary which major has five and which has four? Then either make two recipes, or when you use the one recipe, make use of the heart←>spade swap buttons of the Recipe Panel to change it up on the fly. If you choose to make two recipes, you can put them into a smorgasbord to get a random-selection effect. An advanced topic indeed, but doable.

The next two recipes are similar to the previous two, but with more points in responder’s hand.

1NT opener, partner has invitational strength and is five-five in the majors. (page 345)

1NT opener, partner has invitational strength and is five-four in the majors. (page 345)

And now the same, but with even more points in responder’s hand. Notice how seemingly small variations radically alter the possibilities.

1NT opener, partner has game-forcing strength and is five-five in the majors. (page 346)

1NT opener, partner has game-forcing strength and is five-four in the majors. (page 346)

1NT opener, partner’s best suit is a long minor. (page 346)

Conducive to a 2-spades response bid asking opener to bid 3 clubs, after which responder will pass or bid diamonds, depending on which long minor they have.

1NT opener, partner has invitational strength and a strong six-card minor suit. (page 347)

Since the book said “strong” I took it to mean “good” and not just long. This is a good opportunity to showcase how to put a “good” suit in a recipe. This topic is covered in the user guide, but let’s see it in action here.

Use “H” placeholders to request honors in a suit. Use “G” placeholders to request A, K, or Q in a suit. Armed with those two placeholders, you can specify a “good” suit by both common definitions—2 of the top 3 honors, or 3 of the 5 honors. See the recipe, and be amazed. Two chapters of the User Guide explain good suits, and the curly-brace and square bracket placeholders for expressing random selection (“either this, or that”). To summarize, curly-braces make the generator choose between expressions in different suits within one hand; square brackets make it choose between expressions in one suit within a hand. So in this recipe, we have specified that one minor suit or the other will have six cards, and that the suit that has six cards will have a good suit by one definition or another.

Non-programmers may prefer to design four recipes to express all of the permutations contained within my one recipe, and to collect those four into a smorgasbord for random selection. Or, conversely, to run screaming from the room. But I think that, with sufficient practice and a full fortifying flask, anyone can master the tricksy little placeholders.

1NT opener, partner has a six-card major and enough points to be interested in slam. (page 347)

Finally, our favorite thing: a potential slam that you don’t have to be J-Rod Smeckwell to recognize. Why can’t they all be like this?

Believe it or not, there are three more pages of Jacoby Transfer wisdom in the book after that. But I cleverly limited myself to pages 341-347 because, after that, stuff gets real. It tells you how to deal with interference, and it covers responses to 2NT and 3NT opening bids. Those are super-important topics, but my brain has turned to mush by now and I’m guessing you might have become enmushed a few recipes ago. I’ll save pages 348-350, and some “finer points” pages, for a separate and no doubt equally glorious blog post.

Until then, happy dealing!